For designers and product developers, technical specifications for knitted products can be time consuming. Miscommunication during the prototype phases of design development is not uncommon. Knitted stitches can be misinterpreted, stripe lay outs misaligned, and garment measurements altered due to fabric weight and gauge. These variables cost time and material resources. Where protos arrive with errors, more materials are required and wasted, and more carbon emissions are used to transport second, third and fourth protos back and forth. During their webinar, Shima Seiki proposed their solution to this, utilising their SDS-ONE APEX design system.

Apex is a design system unique to Shima Seiki, used in fashion and other industries for 3D virtual sampling to create realistic silhouettes based on patterns and textures created from real scanned yarns. Designers can now output this information into specifications, and auto generate design and specification pages. During the second webinar of their series, Shima highlighted this potential for linkage between design and production to realise more accurately knitted samples.

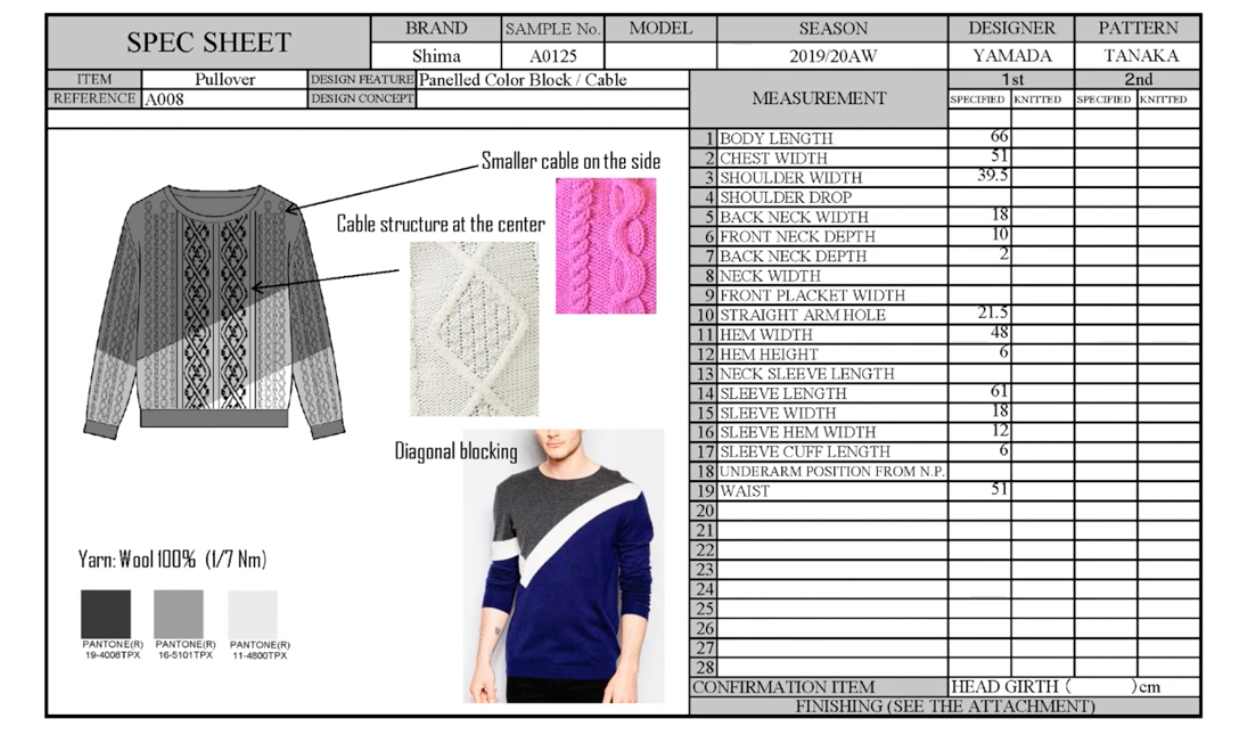

When planning and designing, specification and technical sheets or packs are sent to factories with fabrication details, pattern measurements, drawings, diagrams, colour codes, yarn information, trim details- and much more. This can result in many pages of information. Many design studios use different formats for these documents. This can lead to a lack of clarity and consistency in communication.

Particularly when working with complex stitch structures, time consuming CAD work is necessary for designers to draw stitch placements and shapes. These drawings can be misinterpreted as they are not usually representative of stitch for stitch fabrics.

Confusing things further, across the knitting industry and globally, knitted structures have many different names. What may be known to one knitter as moss stitch could be known to another as seed stitch. This duality perpetuates miscommunication. Even with all this time invested by designers in creating the specifications, manufacturers often find there is a lack of information necessary for production.

APEX software creates knit stitch data when simulating fabrics and this data can be sent directly to factories. Apex software can output design data directly to specification sheets. Not only could this improve accuracy of communication, but it could save designers and product developers time. 3D virtual sampling before requesting the first proto means fabrics can be digitally ‘knitted’ in the correct yarns and gauges, meaning visual decisions can be made before actioning material protos based on specifications alone.

How to create a tech pack using APEX software

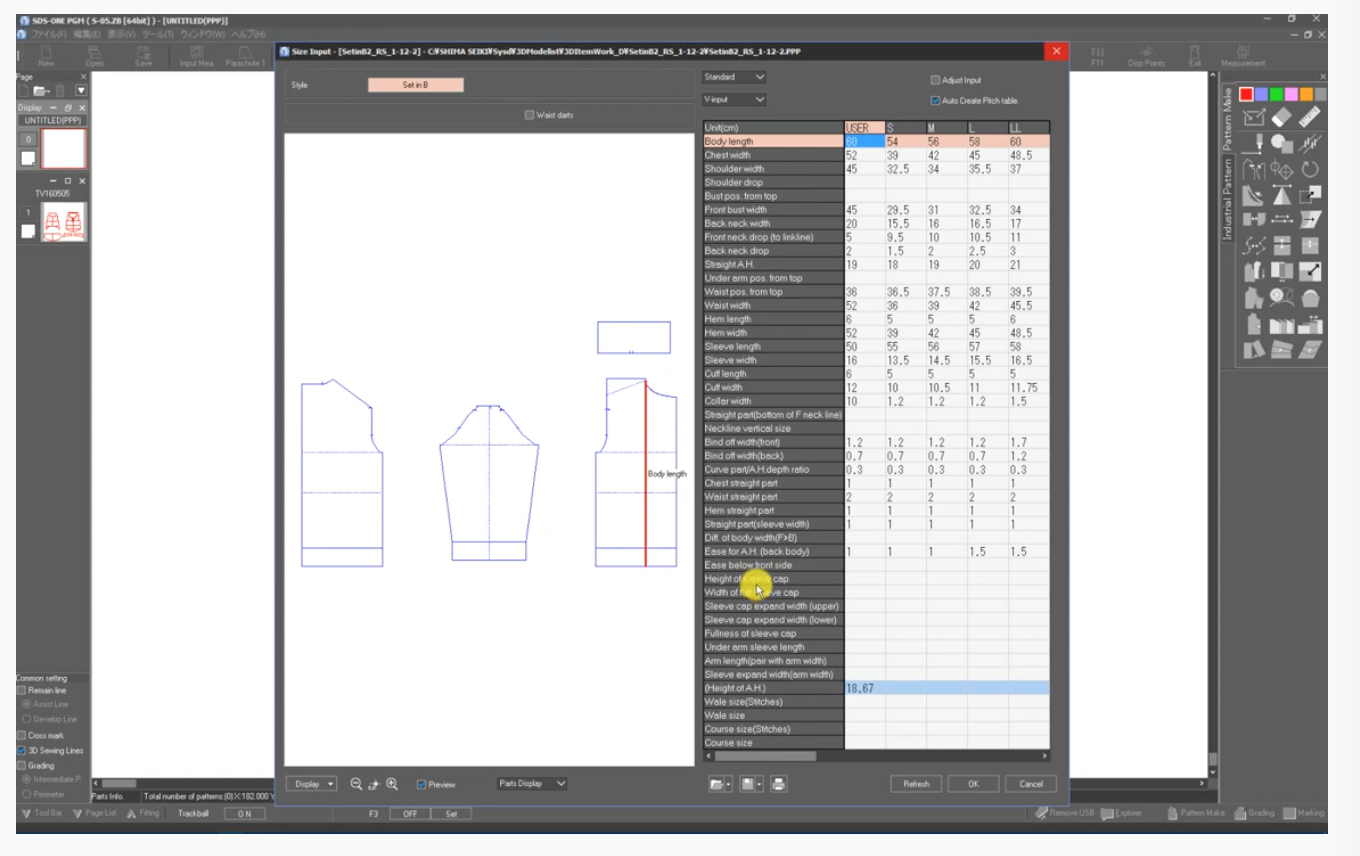

Developing the pattern

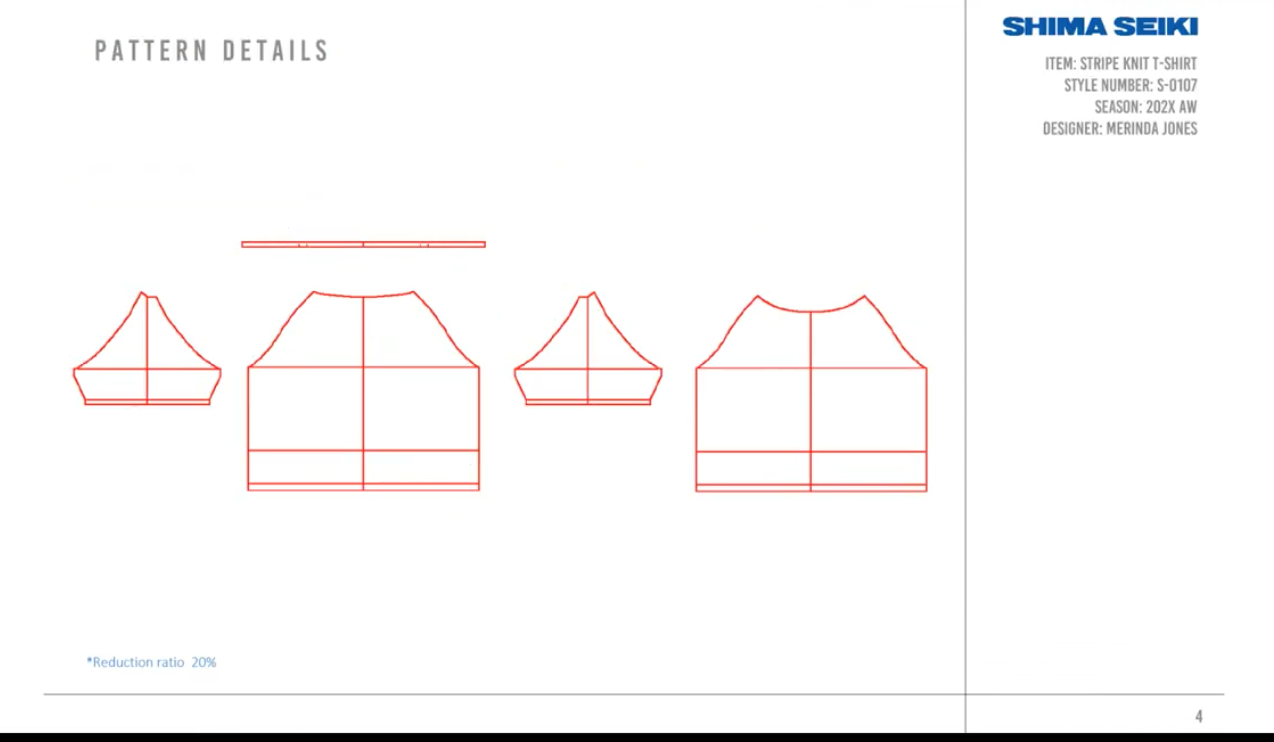

The process begins with the garment pattern image. Apex can auto output patterns by inputting spec measurements, or patterns can be amended and edited from within their library of pre-created patterns. As measurements are added to or edited within the measurement table on one side of the screen, the pattern pieces are visually amended on the other side, so designers can clearly see the impact of each amendment. The table of measurements can be exported to technical specification sheets, as well as the flat pattern imagery.

For those designers with less pattern cutting experience this is a valuable support during the silhouette development phase. Often measurements are altered by designers without a wider understanding of the impact these changes have on other areas of the garment. Apex works this out for designers, increasing the potential for a successful first proto.

Textile placement

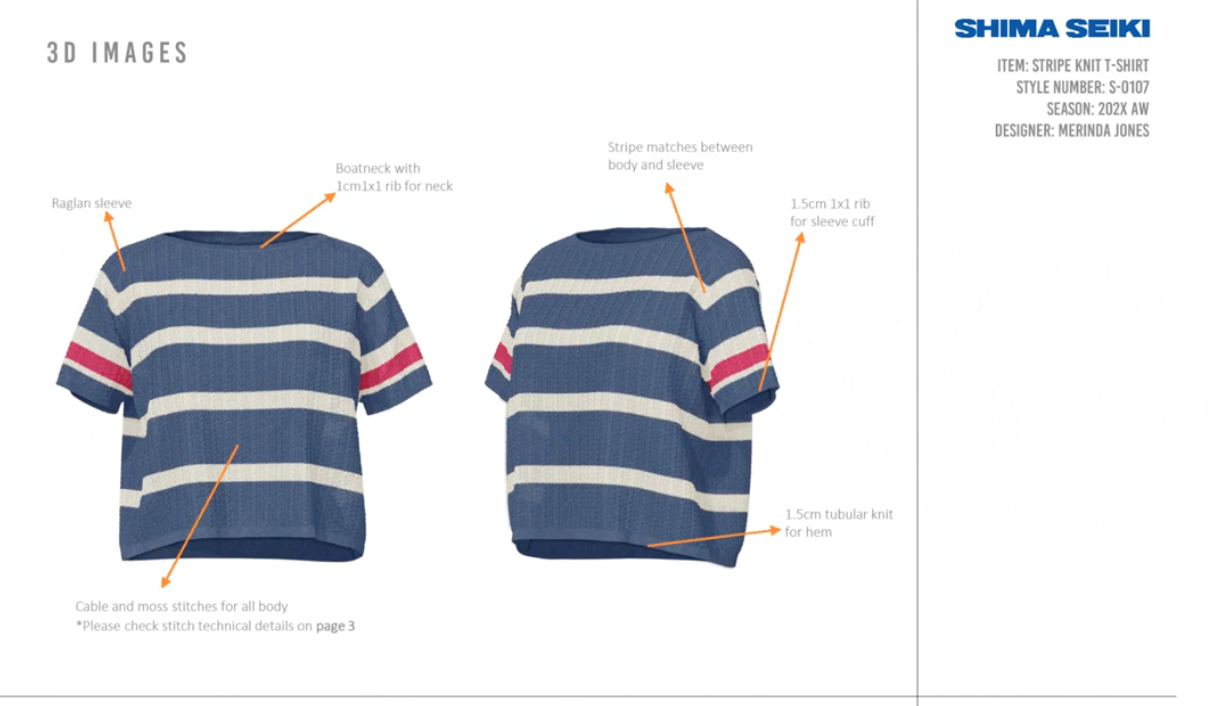

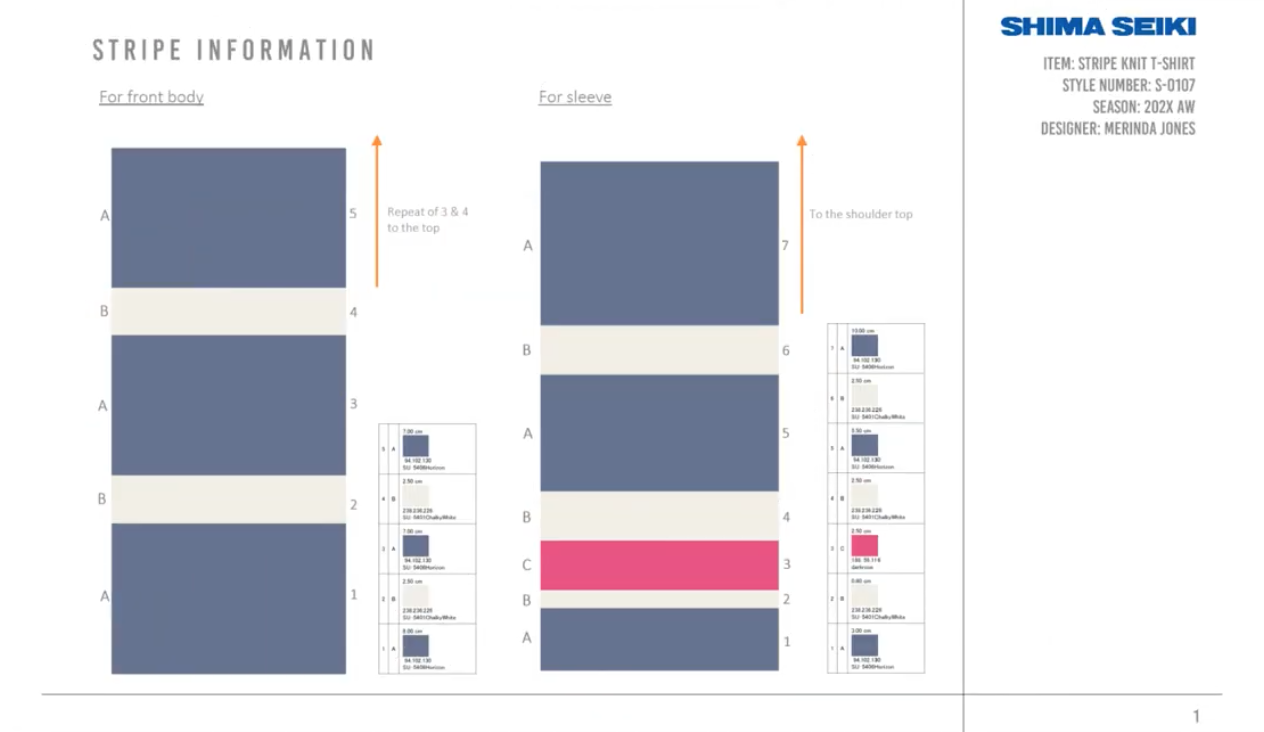

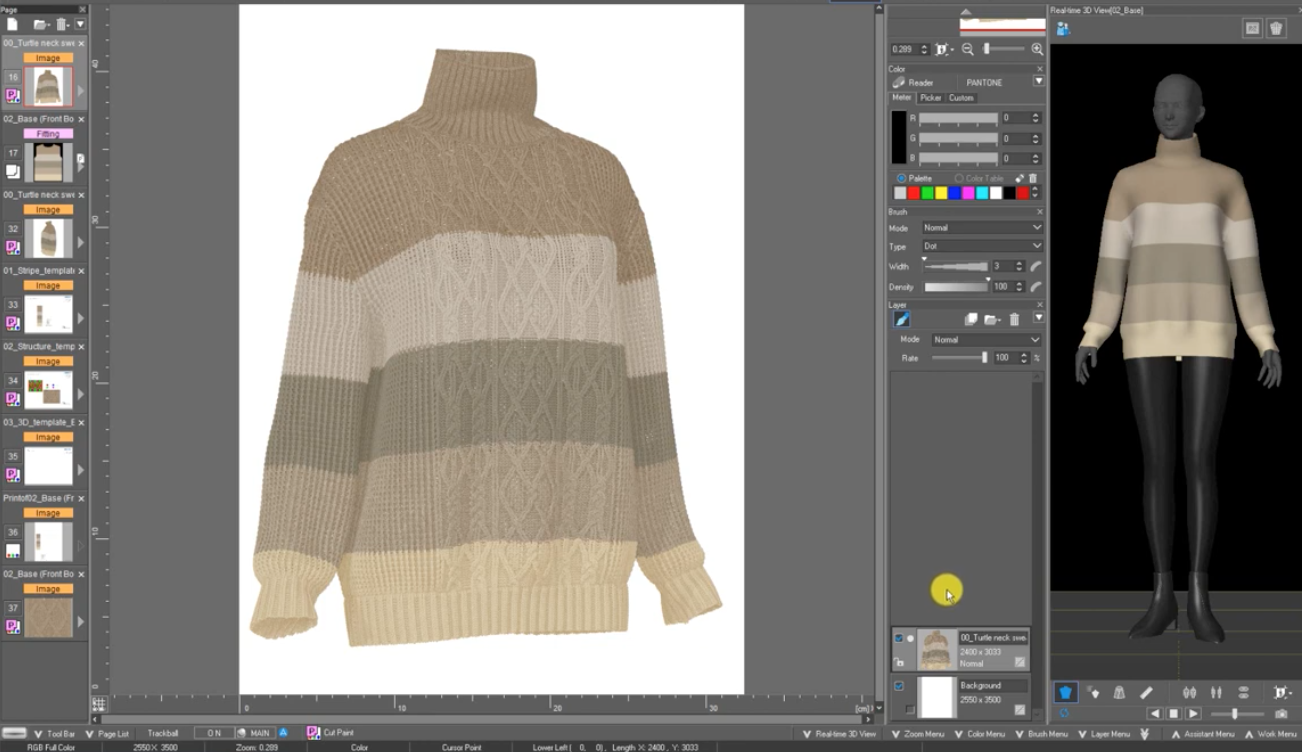

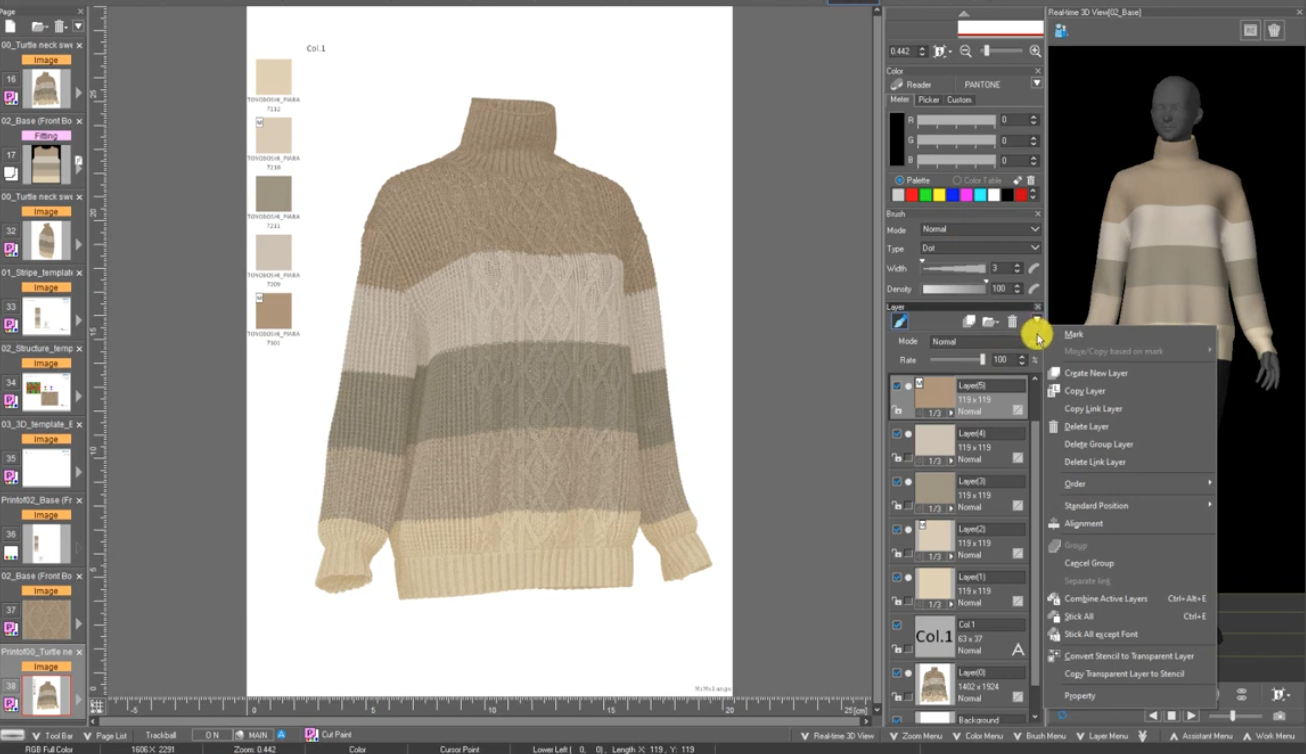

Next, each pattern piece can be individually customised. Stitch patterns, stripe lay outs, colours and yarns can be allocated to each piece and virtually simulated at the same time. This information can be visually outputted by saving the 3D virtual sampling image and outputting as data.

Garments can be viewed in real time on avatars too, essentially creating a 3D virtual fitting experience. Stripe settings can be checked, and stitch placements reviewed before outputting the data. Because APEX generates 3D samples using the exact number of stitches and rows used in real life, simulations are more accurate and reliable than flat drawings.

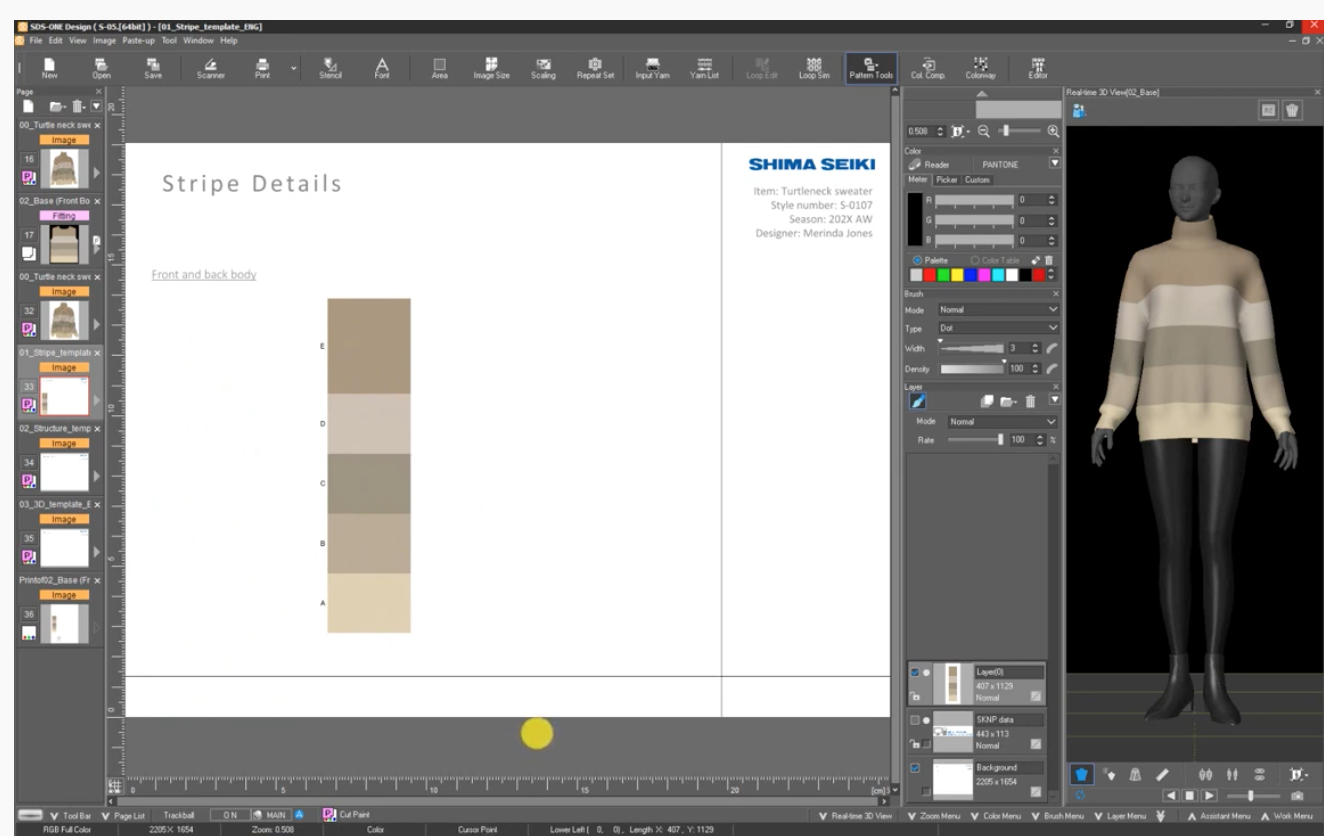

For fabric focussed information, data can be pulled from the development process along the way. For example, when working on stripe lay outs for each pattern piece, the depths, colours, yarns and placements can all be auto outputted onto a single design sheet, removing the need to create diagrams from scratch.

Communicating structural information

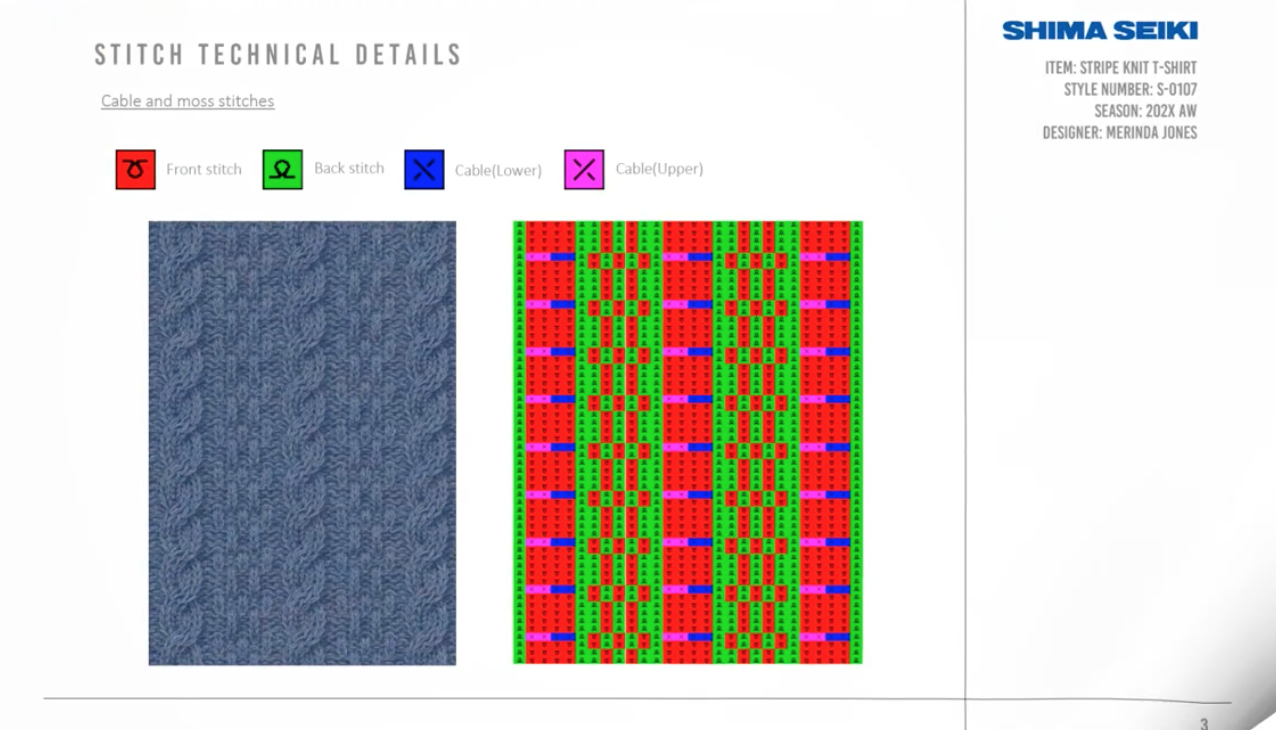

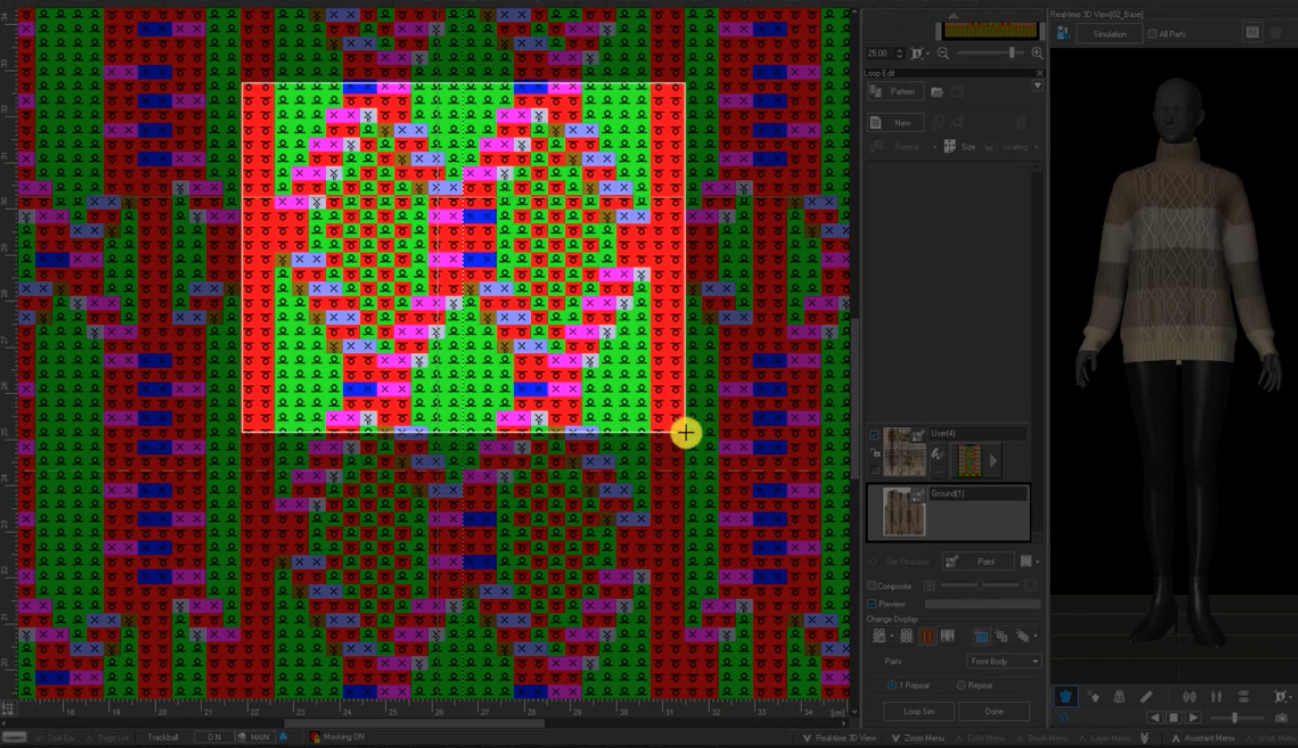

Apex auto generates knit codes for structures created within the software. Each colour code in the stitch chart represents a stitch type. These codes can be interpreted and translated into machine software by technicians. In this way, higher levels of accuracy can be achieved.*

This data allows factories to interpret stitch structures comprehensively, and the potential for misinterpretation is reduced. The stitch charts along with their codes can be saved and added to spec sheets along with rendered fabric images, communicating fabrics both aesthetically and technically.

(It should be noted that there can be issues when translating stitch for stitch designs to Shima’s knit machine software ‘Knit Paint’. It is possible to inadvertently design structures within the software that are not actually knittable on the machines, so this is something to be aware of.)

*The knit codes in Apex are unique to Shima. For example, red is front bed, green is back bed. Other machines may use different codes, so if factories are not working with Shima machines, translation of the codes may be required. It is therefore important to check with factories before development what software and machines they are working with.

Of course, some fabrics may not be knittable on certain machines, and some yarns may not tolerate certain stitches and tensions. There is still the need for physical sampling. But this clarity instilled from the start of the process brings focussed communication. This information can be sent to factories and discussions can be had before making begins. Obvious errors or issues can be realised and amended digitally before moving to sampling, potentially resulting in less wasted proto garments.

3D rendering of garments

Flat drawings can be time consuming. Whilst flat drawings can work well for many garments, fabric details such as complex cables and silhouette elements such as rippling in the draped fabric can be time consuming and complicated to draw- rarely emulating the true tactility of the final fabric and garment.

It is possible that Shima’s 3D rendered imagery of garments could remove the need for flat drawings. Avatars can be viewed at every angle, and images saved. This allows front, back and side views to be captured and added to specifications. This, alongside the previously mentioned pattern piece images gives enough information without the need for opening other software and creating flat drawings.

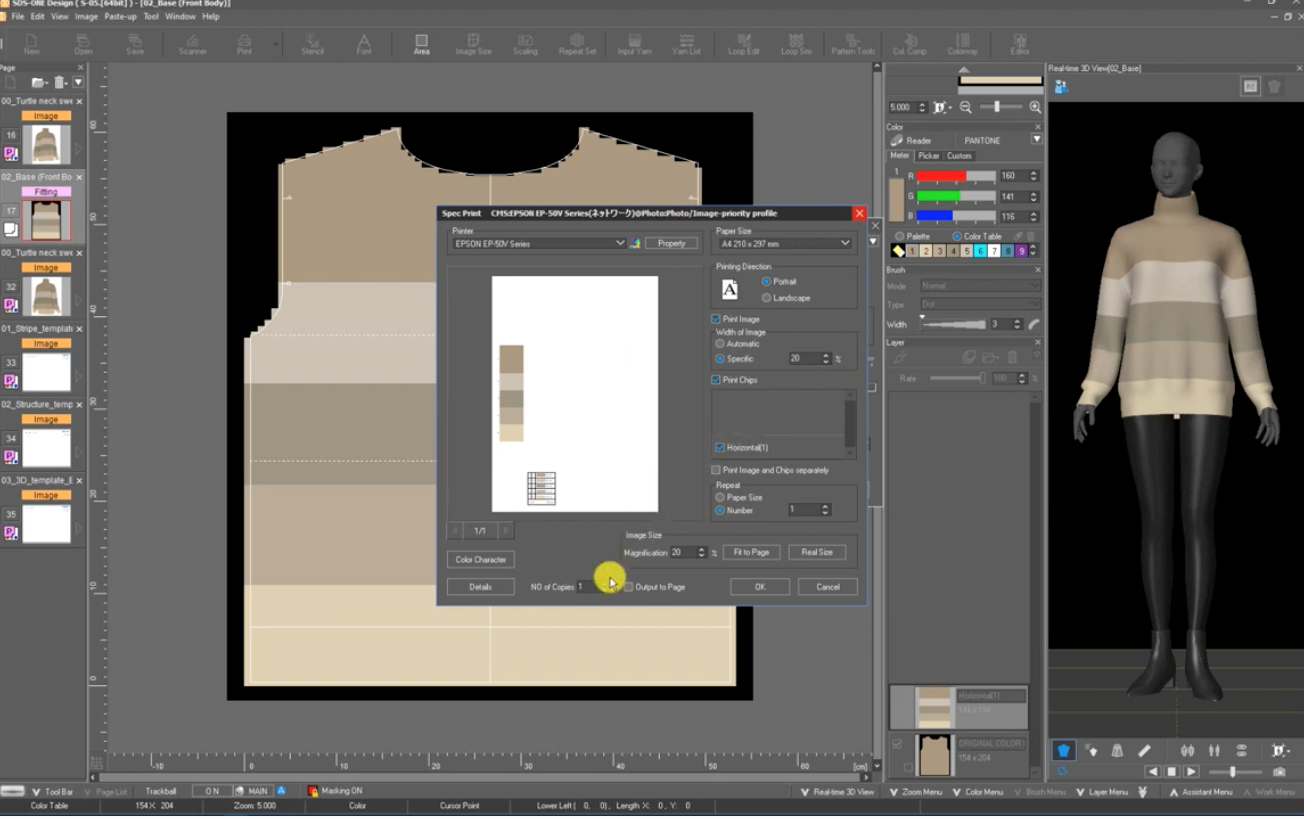

Specification generation through print functions

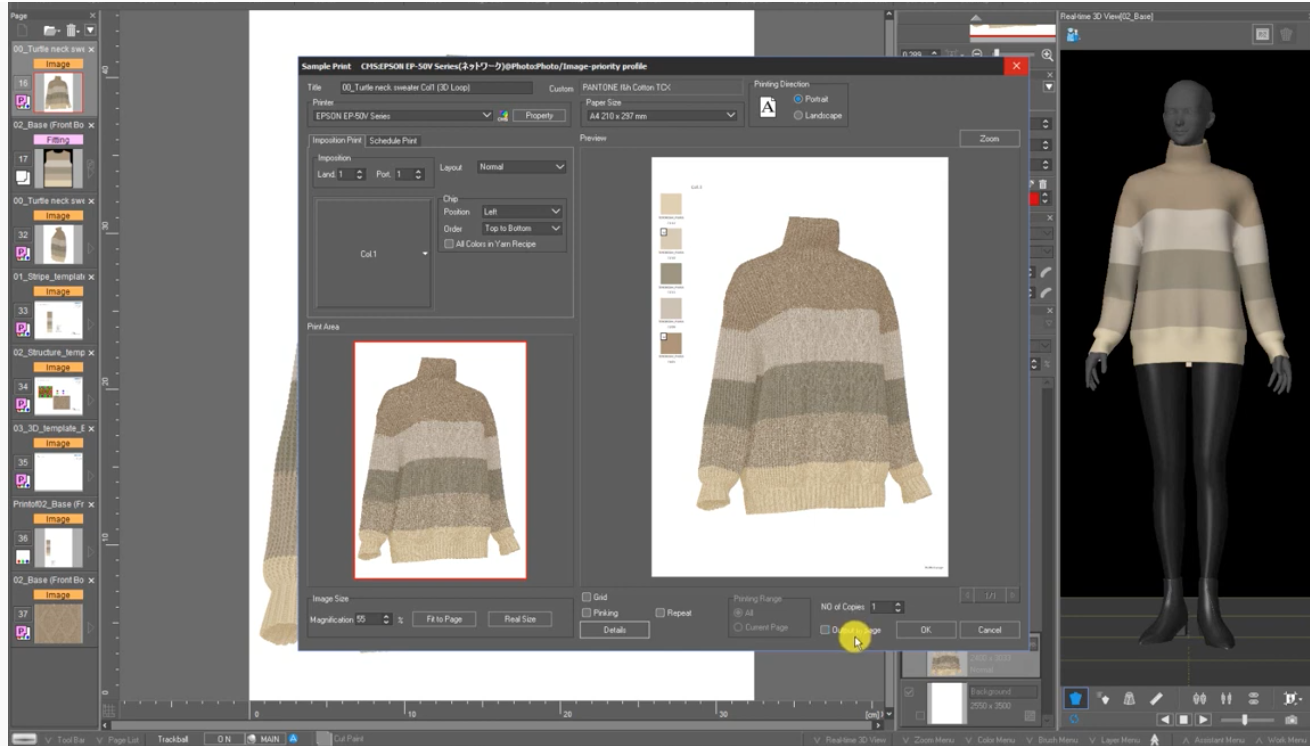

Simple as it may sound, another valuable tool shared within the webinar was the auto print function within APEX. After 3D rendering a fabric or garment, the designs can be outputted to print page layouts which auto generate colour chips, Pantone codes, yarn information and many other details the designer wants to include.

Especially when under time pressures, it can be easy to mistype long colour codes, or misassign names. This software feature makes including these details easy and accurate. This could save designers and product developers a lot of time, and errors in manually entering data could be erased.

There was certainly potential for time saving presented within Shima’s second webinar of the series. In terms of design and product development ‘admin’ such as yarn and colour data input, stripe ratio lay outs and flat drawings, the APEX design system offers functional and accurate solutions.

In terms of communication with factories and accuracy in production, the webinar really spoke for itself. It is clear that this truly knit focussed software offers the knitwear design community opportunities to visualise their designs before production and understand more about the products they are requesting from factories. This in turn could set up factories in strong stead to achieve high quality first protos, replicating the vison of the design team.

The potential for less proto samples, less material waste and less carbon emissions is held within this software. It will be interesting to see whether this potential can be fulfilled in practice.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.