The London Design Festival took place in the British capital last month. We were invited to visit Creative Unions, an exhibition by recent Central Saint Martins graduates in the Lethaby Gallery.

Creative Unions was launched in the spring of 2017 in light of the socio-political situation of the time. Trump had just been elected and the implications of Brexit were becoming more evident. In a climate of division across countries and continents, this initiative aims to unite and promote all forms of creativity.

The exhibition is a collection of responses to our current socio-political climate, sometimes offering solutions for a more responsible future, sometimes giving the viewer a space for reflection, or considering the implications of dystopian scenarios. We are on the brink of major changes in our society and our environment. The pace at which global warming is accelerating is faster than predicted by scientists, its consequences will undoubtedly be significant on the way we live. Design is extremely important at this stage in our evolution because when changes in the environment happen, it will be up to our designers to respond quickly and develop all the tools we need to preserve our quality of life. The general message that emerged from Creative Unions was very clear: we are one people who need to work collaboratively for a more mature and responsible future, where the relationship with our planet is more honest and emphatic, where linear economies are replaced with circular economies and the resources our environment offers are there to be utilised respectfully for everybody’s wellbeing. Creative Unions was curated around various themes that revolved around human connections to the community, participatory design, material identities and the importance of preserving traditions. In a way, these narratives already illustrate the shift of the role of the designer of the future, from a self-centred individual, who is preoccupied with a certain personal aesthetic or image, to a more democratic one, who creates systems and processes for people to have a better quality of life.

Walking into the gallery from Granary Square, the exhibition opens with Data Garden, a project by Florentin Aisslinger. Data Garden explores the relationship between virtual data and the environment, creating a digitally controlled nature. Each time somebody publishes a tweet containing the word “data” or “garden” a seed is dropped in the terrarium on exhibit, whilst the irrigation system is triggered by the word “water”. The development of a successful crop is unpredictable, just like nature, and is influenced by a global virtual mind. It is not clear from the description of the project whether users would be aware of the positive influence of these words in their tweets, but the idea of doing something good for the environment with very little effort is definitely appealing and beneficial on a psychological level to most people.

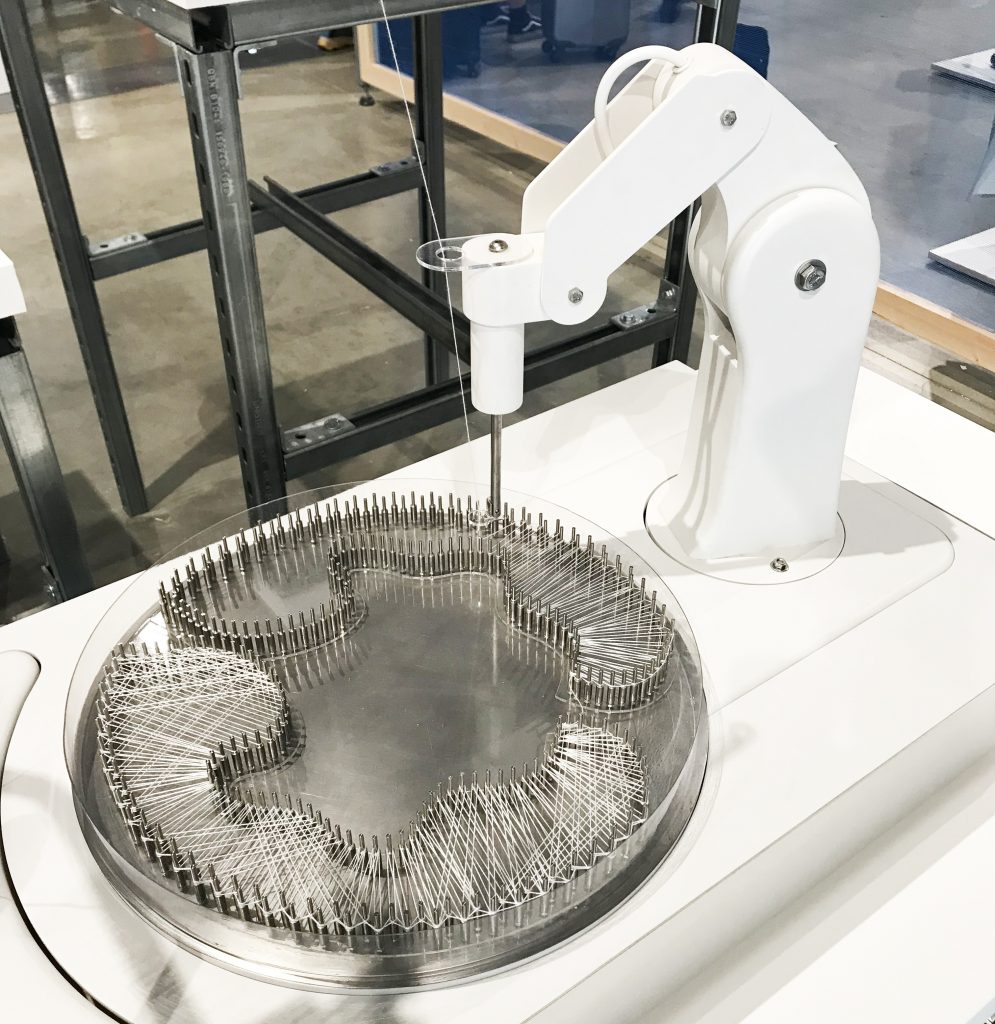

Jen Keane, MA Material Futures, presented This is Grown, an innovative proposal that explores sustainable manufacture for the future. The project was driven by Keane’s “frustration with plastics and a visible disparity between scientific research and design manifestations around ‘natural’ materials”. This sentiment pushed her to investigate more responsible methods of producing materials, such as bacterial cellulose. K. rhaeticus is a strain of bacteria that can produce strong cellulose at high yields, entirely biocompatible and resistant to toxic materials. With the aid of a machine that lays strands of yarn across a surface, the cellulose fabric is grown over this structure to create a certain shape, or pattern piece, which is then used to make a garment or an item. For her proposal, Keane grew a shoe upper which she made into a trainer.

Yohan Gu’s work in the exhibition had a similar social sentiment. WHEELS4U is a project aimed at helping disabled children who live in rural areas of China. Unfortunately access to assistive products is very limited in these parts of the country, probably because of their remote geographical location, so Gu set off to design aids that would improve mobility (and the general quality of life) for these young citizens. WHEELS4U is a low-cost wheelchair made from discarded bikes, recycled washbasins and locally sourced materials. In a beautifully illustrated book, Gu clearly describes her project, where to source recycled bike parts, training people to assemble the products and sourcing local materials to reduce costs where possible (for example, using rice straw for padding on the seat). WHEELS4U has a simple, clean design that is not just functional, but that also is aware of their young consumers. Instruction manuals and packaging are also designed for people who may not be able to read, with a minimal, uncomplicated aesthetic.

Another project that dealt with the issue of waste disposal was by Katie-May Boyd, Foreign Garbage. The beckoning cat, or Maneni-neko, is central to Boyd’s work and it is a symbol of a typical “Made in China” export. Boyd explains that until recently, 30% of the rubbish produced by the UK was sent to China to be disposed of. Earlier this year, the nation enacted a ban on all foreign rubbish imports, generating a heavy strain on many country’s infrastructures. In Foreign Garbage the beckoning cats are manufactured using expanded polystyrene, a packing material that is made in China and that is usually sent back there by many countries to be disposed of. The project highlights the absurdity of the costs and the environmental impacts caused by this unnecessary movements of waste materials, offering a symbolic solution to an ever growing problem.

So far we have presented methodologies that design will explore and evolve into the near future, from the creation and refinement of new manufacturing technologies to a more intelligent disposal and up cycling of materials. There is also another aspect that has existed for quite a long time but that is becoming increasingly relevant – collaborative (or participatory) design. As consumers of a certain product or service, we often have very little input in the design process, so we often end up becoming passive users of somebody else’s ideas or vision. Research shows that collaborating with the target audience in the creation of a certain product actually results in more original ideas, so this is probably why collaborative design is becoming increasingly relevant.

Bupa Streets is a service designed by Charlotte Liebling in response to an industry brief by Bupa. Liebling explains that by 2050, one in five people will be over the age of 60. As an increasing number of our population grows old, we need to find effective solutions to support the elderly in their day-today activities, making sure they remain healthy, happy and independent. Bupa Streets is a straightforward, user friendly proposal that enables people to connect with other members of their community through the provision of certain services: for example a gardener may offer their skills and at the same time meet their neighbours, an artist may organise some drawing classes with tea and coffee at their place. All these activities are aimed at building a sense of community but also an appreciation of each individual person’s self worth, which are crucial elements for the long-term life of a thriving community.

There were more works, more projects that we could talk about here, more than we have space for unfortunately.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.