Simon Cotton, CEO of Johnstons of Elgin and Carla Woidt, founder of Wolfgang Scout came together on day 2 of the ReWire Sustainability conference to discuss how ethos based decision making could impact the fashion industry across every level.

Poised at opposite ends of the ‘business structure spectrum’, Wolfgang Scout and Johnstons of Elgin could be seen as incomparable. But it was on the grounds of their shared commitment to brand ethos that Simon and Carla shared their thoughts on how ethos can – and should – impact decision making processes.

With no joining fee, the ReWire Sustainability conference organised by MOTIF spanned three days, from February the 24th to the 26th. The event line up offered panel talks discussing issues from water footprints to sourcing sustainable viscose. Slotted between the wider ranging discussions led within panel conversations were the ‘Fireside Chat’ segments, offering opportunity to hear a relaxed conversation between industry leaders. It was within a ‘fireside chat’ that Simon and Carla shared their thoughts on the value held in brand ethos when approaching sustainable design and manufacturing.

Served by their local river, for 223 years Johnstons of Elgin has produced knitted textiles and knitwear. As one of the first mills to work with luxury fibres in 1851, Johnstons has grown into a luxury lifestyle brand with a unique business model, focussing on fibre all the way through to finished products.

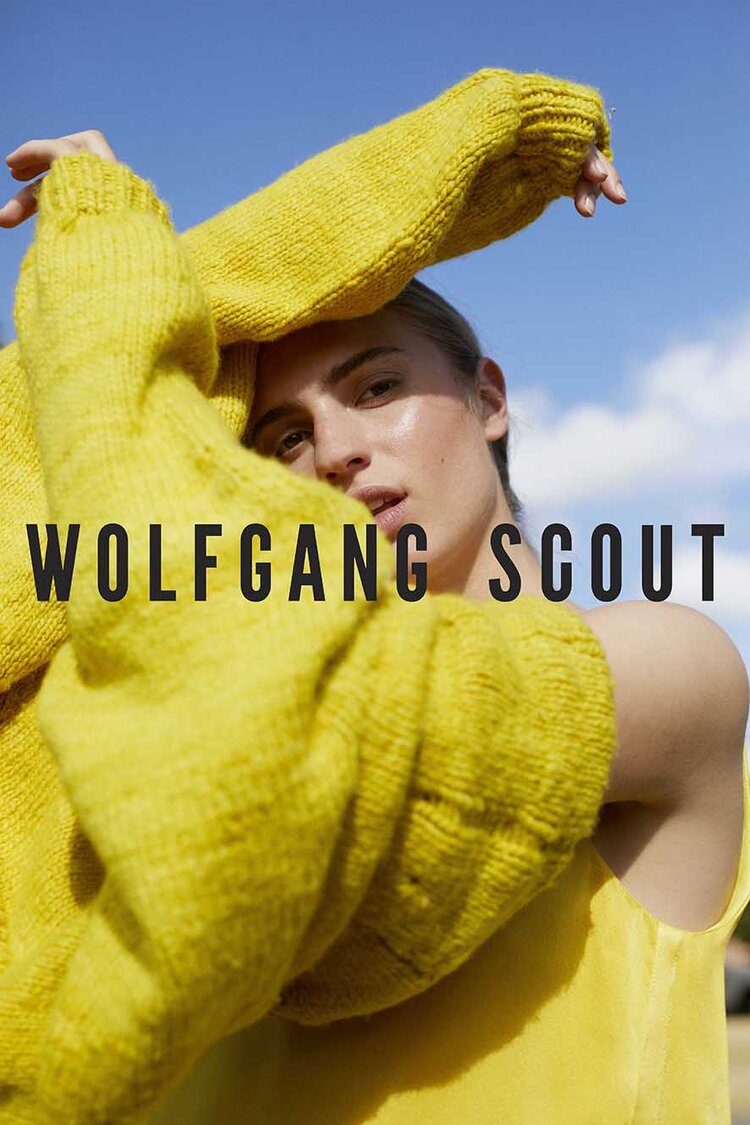

A comparatively small brand, Wolfgang Scout has a unique approach to knitwear creation. Designing hand knitted, often made to order knitwear, their products made from Australian Merino Wool are fully traceable and dyed using non-hazardous, non-chrome, low impact dyes with minimal water wastage. Their ‘slow fashion’ methods mean over 50 hours of handcrafted skill are often contained within each garment.

Though their respective brands differ in age, size and scale, during their conversation Simon and Carla shared a joint motivation for the preservation of skill succession in local communities, and achieving ethical, sustainably made products by upholding their finely tuned brand ethos’ at every level.

How can brands both large and small affect industry wide change whilst also paving the way for others?

Together, Carla and Simon agreed that small and large knitwear brands can each have their own unique impacts, shifting mind-sets and affecting change.

Whilst start-ups and smaller brands such as Wolfgang Scout may not have the industrial ‘clout’ to demand change of large corporations, Carla explained that their power lies in an ability to pivot, adapt, and implement ethical and sustainable practices from the outset.

After working within the fashion industry for many years, Carla built Wolfgang Scout based on a love and appreciation for Merino wool as a natural fibre. Over a year of research into every aspect of her supply chain through testing and seeking out the best options took place before Wolfgang Scout launched. The brand therefore has an ethos built on education at its core.

Growers, scourers, spinners, dyers and manufacturers must engage in an improved process in order to impact at an industry wide level. For Carla, this was something she embedded from the beginning. With no capacity issues, small brands like Wolfgang Scout can be more nimble in this way, reacting to change and making progress.

For heritage brand Johnstons of Elgin, Simon explained that the relentless nature of fashion cycles makes immediate change within one cycle impossible. Within Johnstons of Elgin it is essential to isolate any problem and work on internal improvements, looking forward and anticipating where they need to be. Simon went on to explain that in this way, changes are applied to their systems when they are truly ready.

Preservation of heritage whilst adapting to innovations is a challenge for CEOs such as Simon because changes must be applied to current systems, rather than built in from the start. The flip side to this comes in the power of heritage as a platform builder, which enables larger brands to have the more challenging conversations and demand changes to wider systems. Large heritage brands have industrial influence that can demand change; with large orders at stake, change is incentivised.

Smaller brands can ‘jump on’ this change, and benefit from the ‘trickle down’ impact.

Becoming a partner within supply chains

In their own ways, Simon and Carla both lead brands that are not just participants in their supply chains, but partners. They take responsibility for and apply their ethos to every decision within the whole chain.

For Carla, this means sourcing local RWS certified wool and following it through the supply chain, from scouring to dyeing. Her aim ‘to smell what the wool smells like in the product- clean- but able to feel the lanolin’ connects her products with their material origins. Building this narrative entwines preciousness in the product, encouraging a need for preservation at a consumer level.

The joy and pride for a farmer seeing their wool realised within a knitted product is a motivating factor within Carla’s choice to use 100% RSW certified Australian Merino. Becoming RWS certified is no small feat, and working with farmers to celebrate the fibres they have worked so hard to produce is a rewarding process that supports and preserves local communities.

With an ambition to use 100% RWS certified wool within Johnston of Elgin products, Simon explained how the demand of smaller brands such as Wolfgang Scout could make this more achievable for larger brands. If demand grows on a smaller scale and infrastructure is developed, this can ‘travel up’.

Can brand ethos have enough ‘power’ to implement change?

An ethos sets standards. An ethos builds boundaries and brings factors of morality and social consciousness into consideration. An ethos has the power to form communities of like-minded people, building teams who can work together to affect change.

Without an ethos, there is only financial incentive to drive decision-making; this is where the fashion industry has gone so wrong.

The removal of hazardous chemicals from the cashmere scouring process was something Johnstons of Elgin was able to drive in their supply chain. Whilst chemical manufacturers had not felt it necessary to reformulate previously, there was impetus to work on chemical elimination if the industry at large demanded it.

Ethos was responsible for this demand, not financial incentive. It would have been ‘easier’ for Johnstons of Elgin to continue with the ‘status quo’, but their ethos demanded better of them and drove positive change. An ethos challenges brands to be better in this way.

If all brands would prioritise traceability, responsibility, stewardship and credibility, over financial incentive and capital gains, shared gains could be made across industry levels. Ethos could and should be valued and preserved within brands of any size. Wolfgang Scout and Johnstons of Elgin exemplify this.

Wolfgang Scout

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.